Navigating Risk: The Art of Underwriting Contract Guarantees in Sub-Saharan Africa

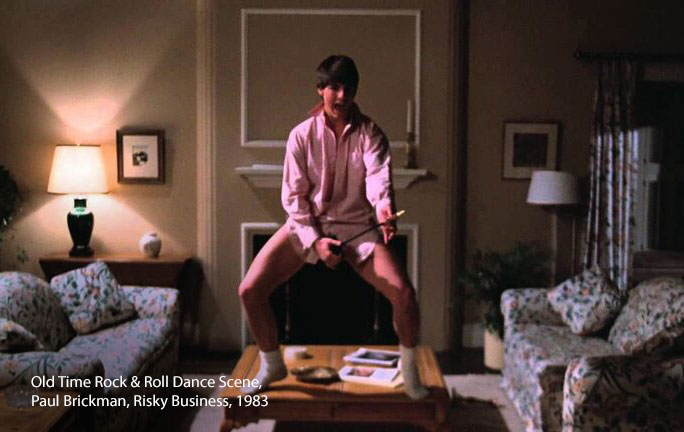

In the world of contract guarantees, our role as guarantors can put us in some pretty exposed situations. Did you ever see Tom Cruise in “Risky Business” dancing in a pink shirt, socks, and undies? Sometimes, we too feel a bit like this. Thinking about it…

Unlike traditional insurance, once a guarantee has been issued, there’s no coming off risk or changing terms. Guarantors are often unsecured lenders – making indemnification a challenge. If a client hits hard times, a guarantor may have to increase exposure, and even inject capital into the client’s business.

The question is – what crazy group of individuals would willingly take such risks?

The answer is – me and my colleagues—a ragtag group of contract guarantee underwriters and administrators with complementary skills, a good sense of humour, and the ability to apply industry-leading risk management to the unique operating environment of sub-Saharan Africa.

Let’s unpack the dark art of guarantee underwriting and you can decide whether we’re aggressive risk takers or just straight-laced risk managers.

What are contract guarantees?

A contract guarantee is a financial product – issued by an insurer or a bank – guaranteeing the fulfilment of obligations under a contract.

Whilst this is most commonly issued under a construction contract (as indicated in the image above), in reality, our clients span multiple industries including civil engineering, building, manufacturing, steel fabrication, shutdown and demolition services, instrumentation, supply and installation of capital-intensive equipment – like diesel generators or lifts – and even IT system implementation.

In fact, any contract between two parties, requiring one party to perform in terms of the contract, could require a contract guarantee.

Looking at contract guarantees differently

Not only do we adjust our underwriting approach based on the respective industry, but the specific project, client and employer jurisdiction also inform our assessment of risk. The particularly complex and real-life example above illustrates the various parties we interrogate before issuing a guarantee.

The risks assessed include country, sovereign, credit, technical, legal and supply chain risks.

Navigating financial landscapes through project finance

Of course, no contractor should ever take on a job without first determining if the employer has secured finance for the specific project. Projects can be self-funded (via company cash flows) or funded via third-party debt. Project finance is a particularly unique form of finance, and is becoming increasingly common for long-term, capital-intensive projects.

This structure does not depend on the balance sheet of the project sponsor, but rather on projected project cash flows. Since there is uncertainty as to whether the project will actually generate said cash flows, lenders often seek to transfer risks beyond the project company – as it’s only a special-purpose vehicle.

Utility-scale renewable energy projects are often funded via this method. One of the ways lenders mitigate output risk on these projects is by requiring a guarantee from the engineer-procure-construct (EPC) contractor, requiring that plant output (e.g. generation capacity) be met by a certain date (e.g. commercial operation date) so that the project can start producing revenue and pay down debt.

These guarantees are normally ceded to the lenders as part of their EPC security package. Ceding a guarantee is ostensibly more onerous than if the guarantee were to be retained by the project company, as there may be different motivations to ‘calling’ the guarantee. Moreover, plant output or efficiency is often excluded from reinsurance treaties – preventing guarantors from taking on such risks.

The EPC contractor will appoint a sub-EPC or electrical and civils balance-of-plant (eBOP & cBOP) contractors to conduct more traditional construction works. The structure and obligations on these contracts are more familiar to contract guarantee providers and, therefore, may be more aligned to their risk appetite.

A Closer Look at Project and Contract Risk

A simple project can be made high-risk by allocating most risks to the contractor, whereas a complex project can be made more palatable by fairly allocating risks between contractor and employer. Specific aspects of a contract we interrogate include:

- Design risk

- Sub-surface condition risk

- Payment method and related clauses (e.g. unit priced or re-measurable contract? Are cost escalations incorporated or is this a lump-sum turnkey project (i.e. date certain and fixed price)? How are delay and liquidated damages applied?)

Contractor designed projects command a higher profit margin, but come at a price – usually that the contact is negotiated at a fixed price with little opportunity to pass through price escalations to the employer, and there are severe penalties for project delays or sub-standard performance.

So, are we aggressive risk takers or just straight-laced risk managers? In my estimation, it’s not binary. We are commercial and risk averse. Whilst we don’t vacillate, we are definitely not unwilling to change our minds.

At stages in the business cycle, we will be risk on, and at other times, closer to risk off. We’ll always attempt to support our clients through the cycle, but may pull back on certain industries, geographies or contract-types.

Reach out if you’d like to discuss how we can support your organisation, or click here to apply online for a new guarantee facility.

More reading

In the world of financial assurances, the distinction between an insurance and a bank guarantee looms large in the minds of many.